Overview of Rickettsia rickettsii and Rocky Mountain spotted fever

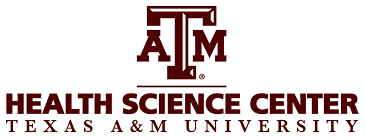

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial infection acquired upon the bite of an infected tick. It is the perhaps the most deadly tick-borne illness (Crimean-Congo hemoragic fever is similarly dangerous) and the severest form of rickettsiosis. Interest in RMSF began in the late 1800s and early 1900s when a mysterious illness was afflicting ranchers and others in the West. The young scientist Howard Ricketts traveled to the Bitterroot Valley in Montana and discovered the link between this deadly disease and the Rocky Mountain wood ticks that emerged every Spring. Vaccines were developed at Rocky Mountain Laboratory to protect Montanans from the disease. In recent years, RMSF has become less common in the Northwest, and more common in the Eastern US. A particularly deadly outbreak has been occuring in the Southwestern United States and North Western Mexico, where the diesease is transmited by the brown dog tick, which can survive in urban settings. In effect, the disease has gone from being a rural issue to becoming a hazard for poorer urban areas. Rickettsial diseases also include endemic (flea-borne) and epidemic (louse-borne) typhus.

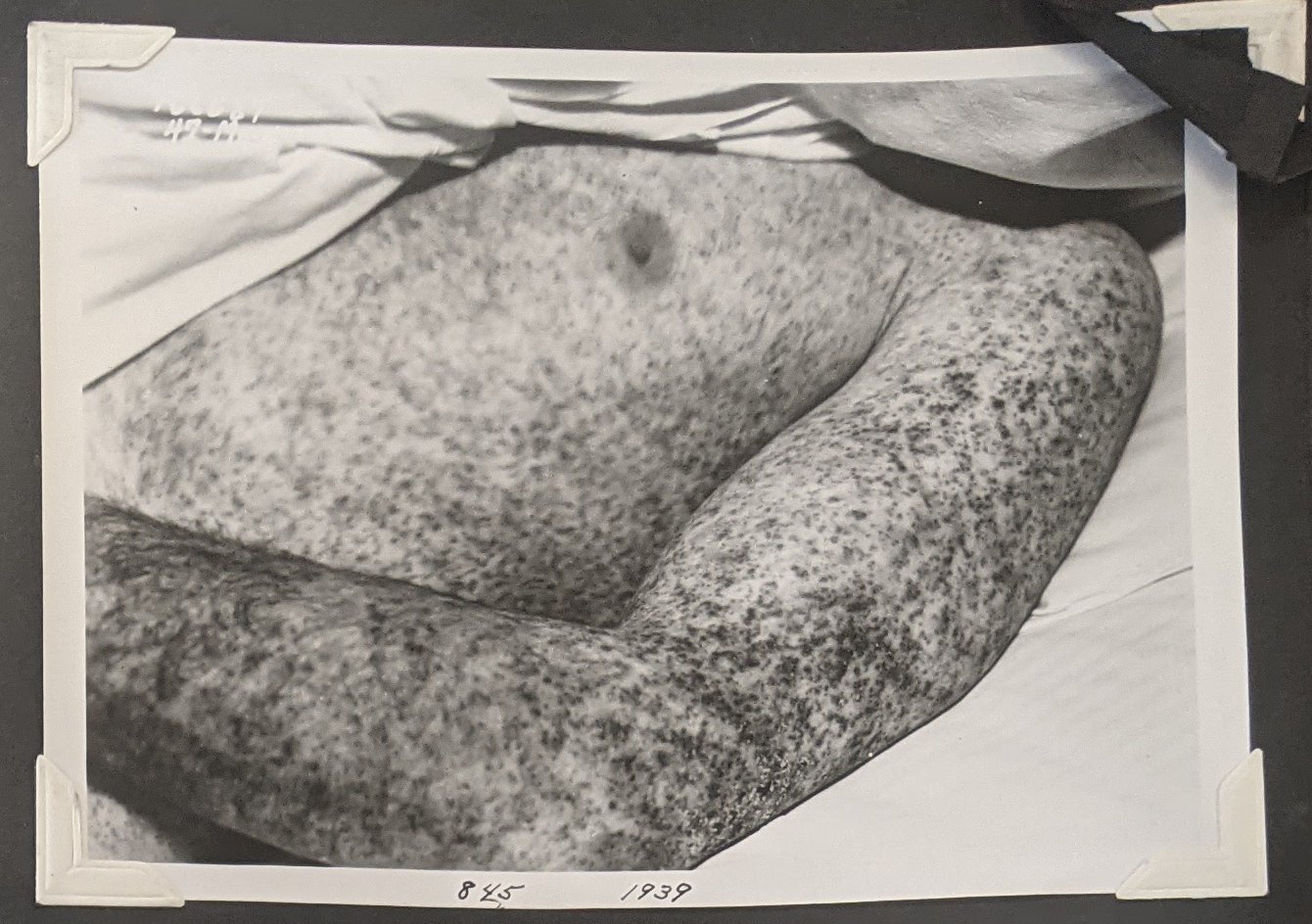

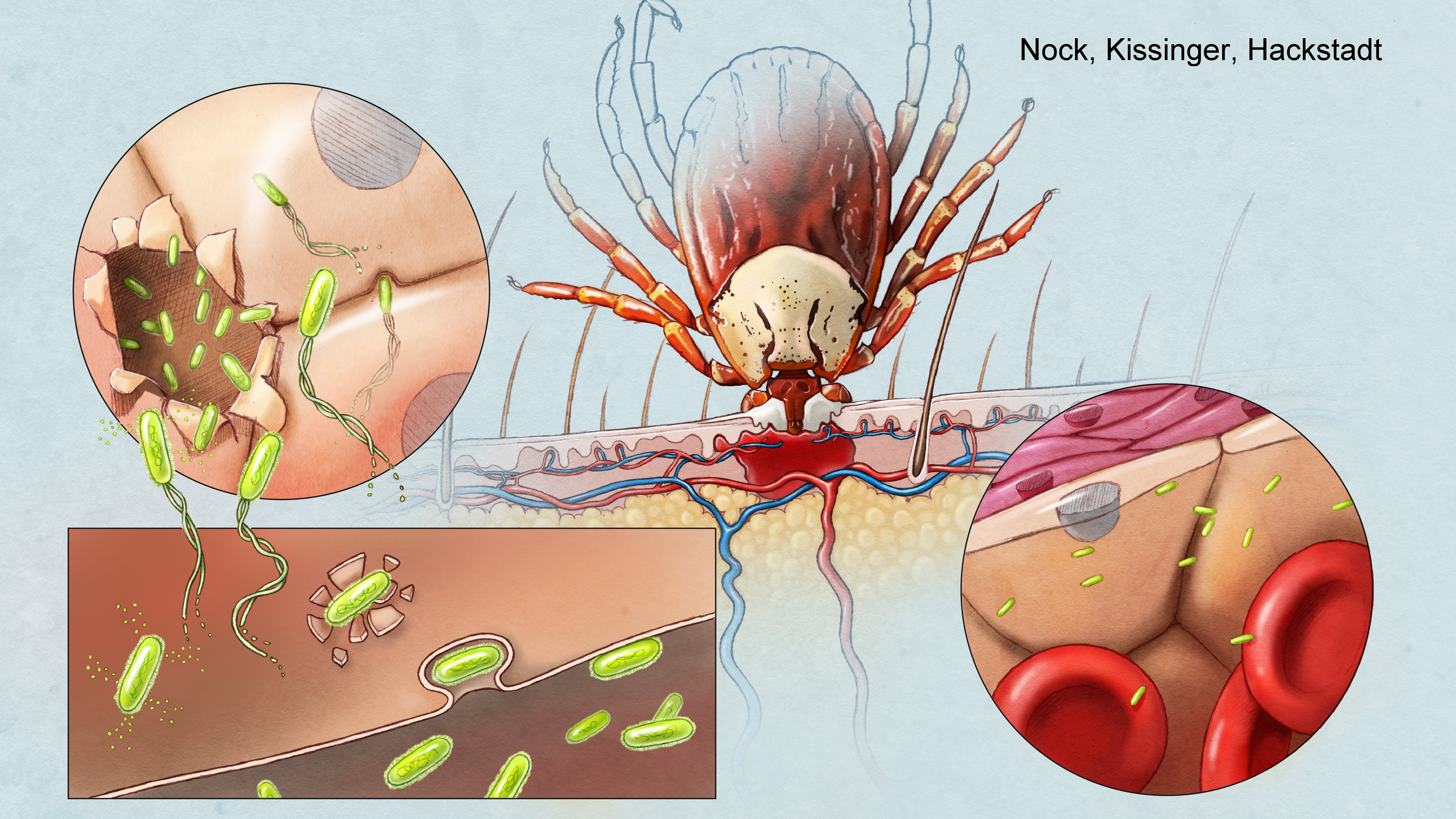

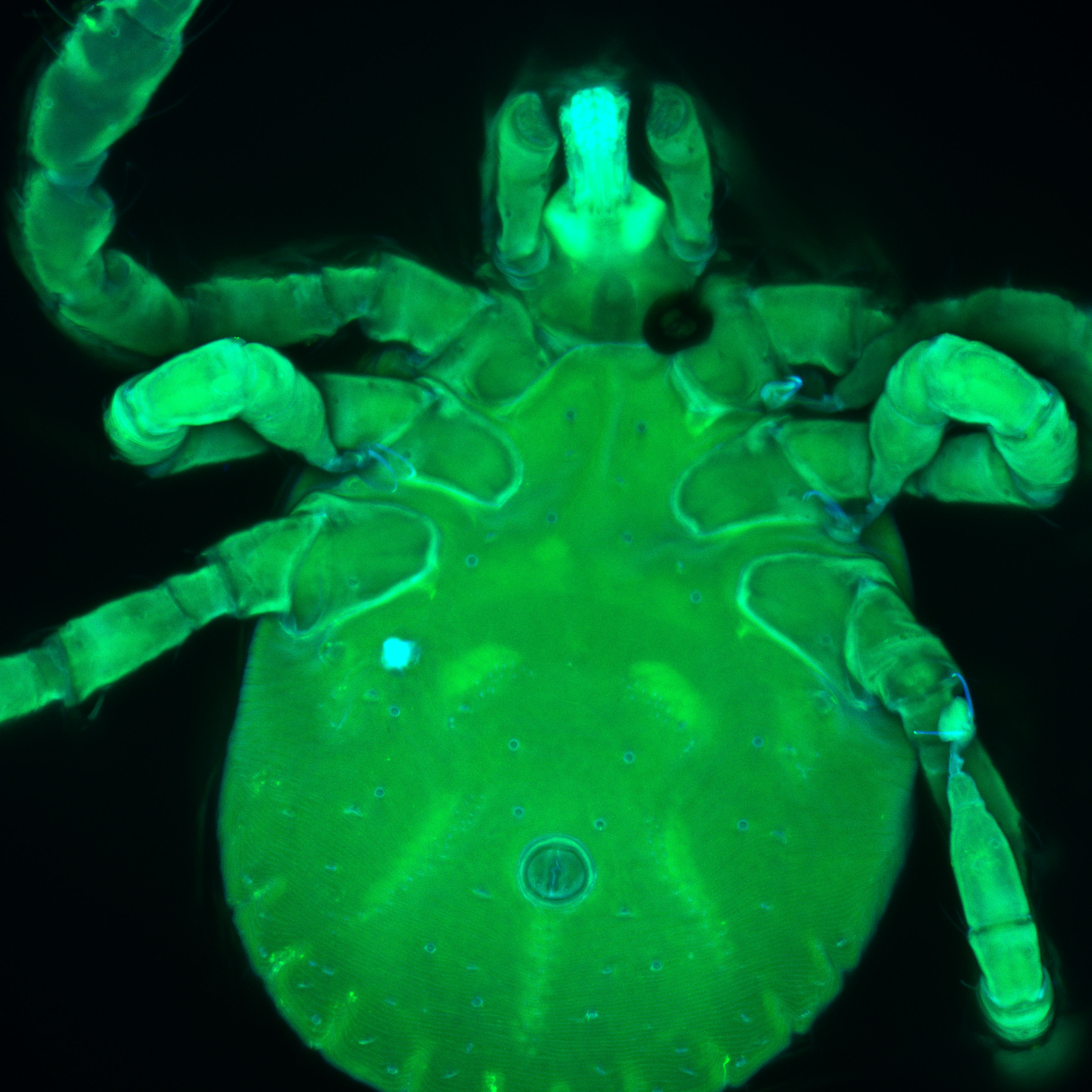

The bacteria that causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever is Rickettsia rickettsii. These bacteria can be carried by many hard ticks, but most notably, the Rocky Mountain wood tick (In the Northwestern US), The American dog tick (In the Eastern US), the Brown dog tick (In the Southwestern US and Mexico) and various tick species of the genus Amblyomma (Brazil). The rickettsia are introduced from the tick into the bite site, where upon the rickettsia adhere and invade primarily vascular endothelial cells. They rapidly escape the endosome using several lipases, and are exposed directly to the host-cell cytosol. There, they utilize a type IV secretion system and various effectors to establish a replicative niche. Members of the spotted fever group of Rickettsia are able to subvert the host-cell's cytoskeletal building block, actin, causing it to polymerize into long actin tails or "comets" that push the bacteria into neighboring host-cells. Alternatively, the typhus group of Rickettsia rely on host-cell lysis to spread from cell to cell though Rickettsia typhii is capable of making smaller tails.

Research Interests

Broadly, I am interested in how bacteria interpret environmental signals and integrate those into a transcriptional, biological response. Rickettsia rickettsii must transition from life within its tick vector to a mammalian host where it will multiply and possibly infect naive, co-feeding ticks. These are quite different environments and the rickettsia must sense which environment it is in and respond appropriately to survive!

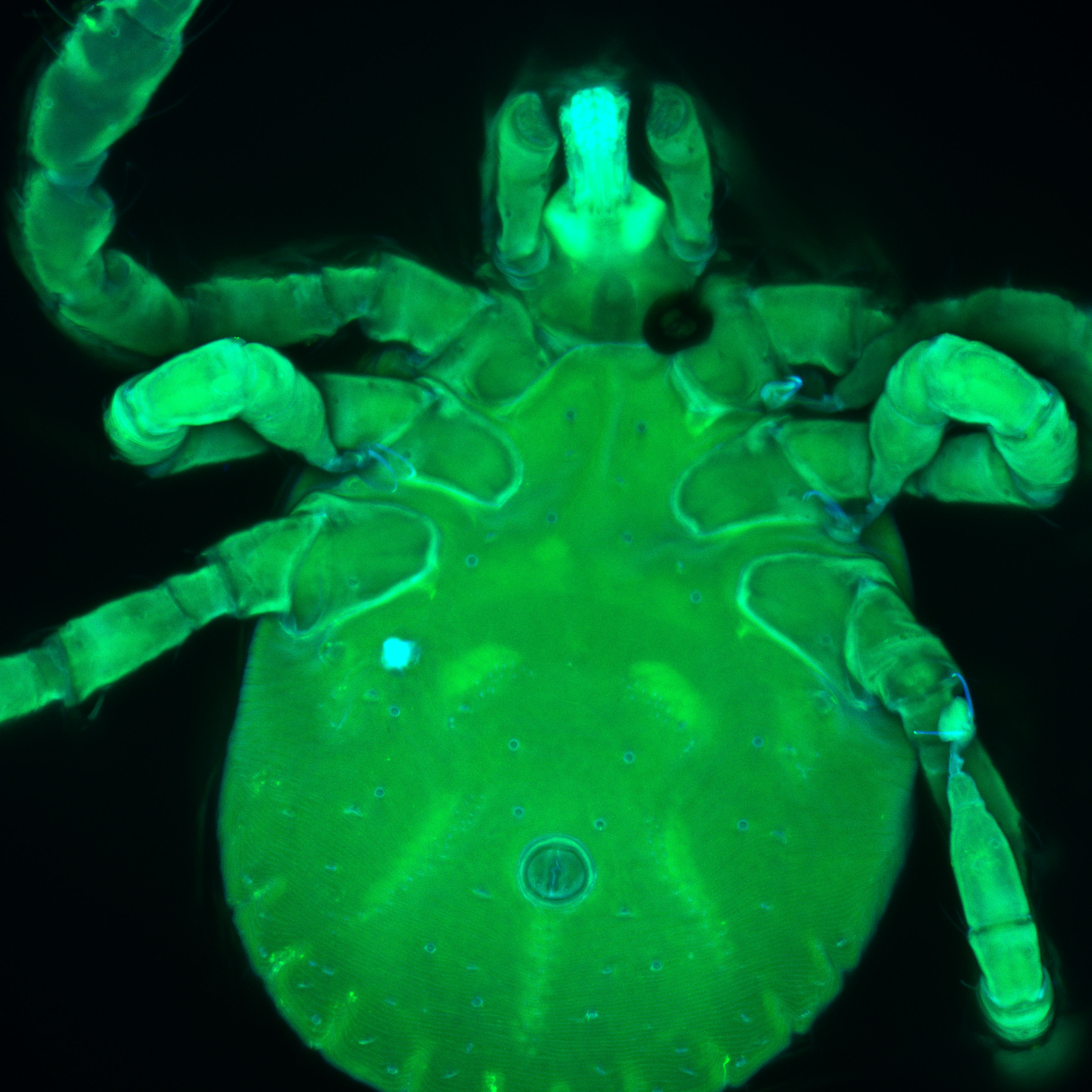

During my postdoctoral studies, I identified a rickettsial gene that regulates motility in Rickettsia rickettsii. This gene, roaM negatively regulates the production of actin tails as well as the production of other rickettsial effectors. As seen above, wild type rickettsia with intact roaM grow to high numbers per individual host-cell prior to turning on their program of aggressive spreading. In contrast, strains which have a truncation or deletion in this gene become "hyper-spreaders". The main projects of our lab focus on the consequences of this regulation for viability of the arthropod vector, and the functions of the genes that are regulated by RoaM.

Opportunities

Our laboratory operates as part of Texas A&M Naresh K. Vashisht College of Medicine. If you are interested in joining as a graduate student, our laboratory participates in the Medical Sciences and Genetics and Genomics PhD programs. MD/PhD and DVM/PhD students interested in research are also welcome. We are currently accepting students for rotations.

Texas Ticks

Notes: In the Southern US, there is some ambiguity in the literature as to whether D. negrolineatus is the same as D. albipictus. They are clearly different if you examine their spiracular plates!

| Species | Dorsal View | Ventral View |

|---|---|---|

| Gulf Coast Tick, male (Amblyomma maculatum) |  |

|

| Black Fern Winter Tick, male (Dermacentor negrolineatus) |  |

|

The Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni)

Notes: This species was the tick originally shown to harbor Rickettsia rickettsii and transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

| Larva | Nymph | Adult Female | Adult Male |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

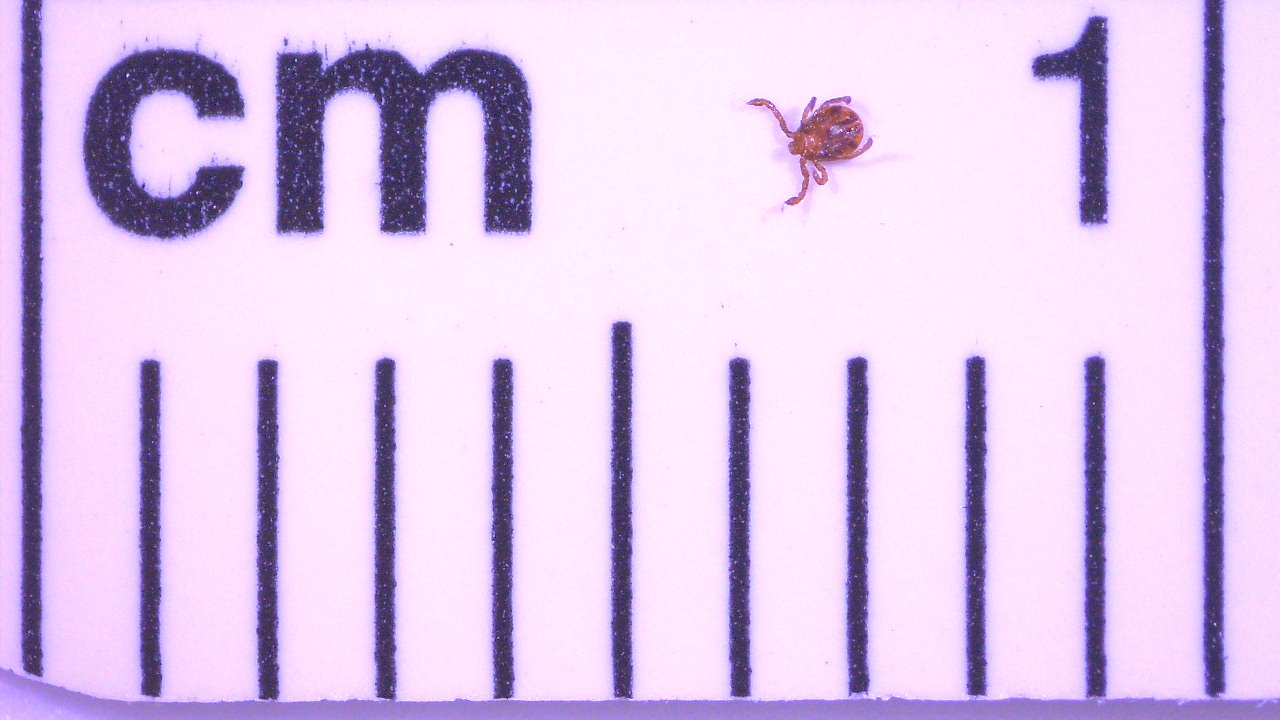

Here's an example of what a fed tick looks like, a closely related American dog tick female specimen from North Dakota (Dermacentor variabilis) (Courtesy of Jag the dog!)

Ticks from the Closter Nature Center and Oradel Reservoir

Notes: Deer ticks (also called Black-legged ticks) can transmit Lyme disease. Only the adults and nymphs (not pictured) can acquire Lyme disease from a blood meal and then spread it to a person via a bite. The bacteria that causes Lyme disease usually isn't transmitted until about 24 hours after tick attachment, but these ticks can spread other diseases as well such as Powassan virus, human granulocytic anaplasmosis (related to Rickettsia, and babesiosis (a parasite).

Asian longhorned ticks are new to the US and all ticks in the US are female due to their ability to reproduce without males (parthanogenesis). These ticks prefer to bite cervids like white tailed deer but can bite people too!

| Adult Female Deer Tick Ixodes scapularis | Adult Male Deer Tick Ixodes scapularis | Larva Asian Longhorned TickHaemaphysalis longicornis | Nymph Asian Longhorned TickHaemaphysalis longicornis |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

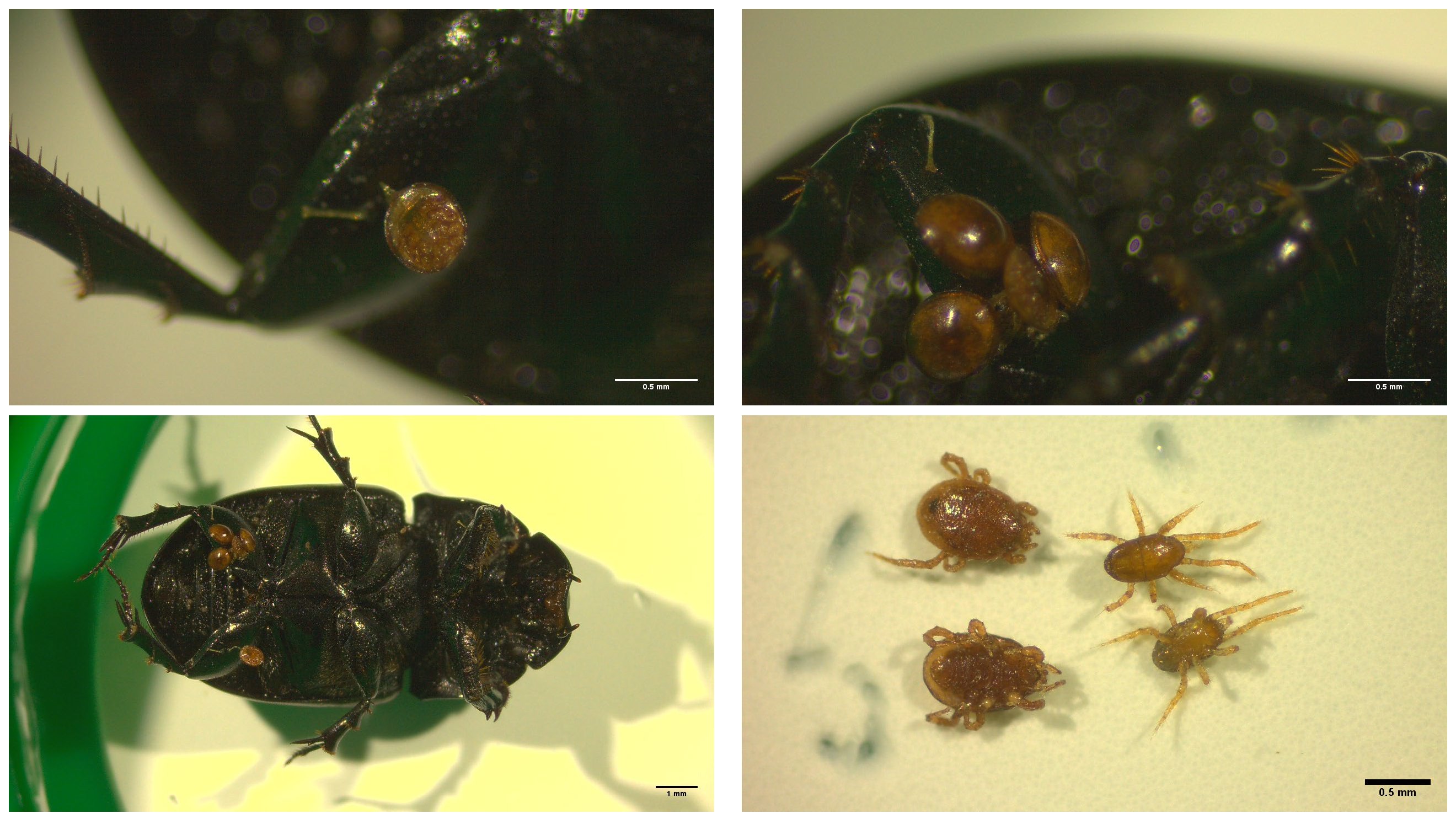

Other interesting specimens

Scarab beetle with phoretic mites, possibly two species!

The PI

|

Adam Nock, PhD I grew up outside of NYC close to where Major John Andre was hung, the Closter horseman rode, and where Washington slept everywhere. I've always enjoyed the outdoors and bugs in particular. I went to Rutgers University for my undergraduate work where I was introduced to biosafety level 3 work in an Anthrax lab, spent some time as a research assistant at Rockefeller University, then went to graduate school at the University of Vermont studying transcriptional regulators in bacteria. I then did my postdoctoral work at NIAID in Montana (Rocky Mountain Laboratories) where I was able to merge my interests in bugs and bacteria, and have now started my own laboratory studying tick-borne diseases at Texas A&M College of Medicine! |

Current Lab Members and Colleagues

| Photo | Name | Role in Lab | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mariajose (Majo) Tarot | Research Assistant | I am from Guatemala. I graduated from Amherst College with a BS in Biology, the University of Oslo with a MS in Health Care Managment, and Texas A&M University with a MS in Microbiology. I am currently a Lab Manager/Research Assistant for Dr. Nock. I enjoy traveling, reading, and photography. My favorite tv show is Avatar: The Last Airbender. | |

|

Sammuel Bennett | Research Assistant | I'm originally from Houston, Tx. I graduated from Texas Tech University with a bachelors in Microbiology and a minor in Chemistry. I am currently a Research Assistant for Dr. Nock. I enjoy hikes, cooking, and reading. My favorite tv show is Boston Legal. |

|

Abigail Schlieker | Research Assistant (Huntley Lab) | I am from Hearne, Tx. I graduated from Blinn College with an associates in Chemistry and Texas A&M University with a bachelors in Genetics. I am currently a Research Assistant. I enjoy spending time with my friends, family, and pets. My favorite tv show is Frasier. |

|

Aidan Burkle | Undergrad | |

|

Alisha Naqvi | Undergrad |

Former Members

| Name | Role in Lab | Current Position / Where are they now? |

|---|---|---|

| Presha Vaghela | MBIOT Student Intern (Spring '25) | Interning in A&M Chem department |

| Mary Smith | MBIOT Summer Internship (Summer '25) | Finishing Masters in Biotechnology |

Contact

Address: 8447 John Sharp Parkway Medical Research and Education Building I - 3102 Bryan, TX 77807-3260

Email: adamnock@tamu.edu

Phone: 979.436.0354